In this episode Gordon talks with Jane Carter, LPC a therapist and private practice business coach about how we handle anger in the context of kindness and compassion. We explore how being “polite” does not always equate to being kind. In fact, sometimes politeness can be a form of anger turned inward. We also explore how expressing our anger in healthy ways can lead to greater emotional intimacy and be an act of kindness and compassion. We also look at how we can confront injustices as an act of kindness and compassion.

Meet Jane Carter

Jane Carter, LPC is a counselor and business coach from Asheville, NC. Jane has spent the last several years in private practice as a counselor and has recently begun focusing more on business coaching, not only for therapists but other businesses as well. Her website is: JaneCarterCoaching.com

Jane says, “As a therapist, business coach, and life coach, I love helping people navigate the path to achieving their goals for a meaningful life. I apply these principles in my own life in the mountains of Asheville, NC, where I’m an outdoorswoman, world-traveler, dog-mama, food-and-wine lover, reader, and coffee-shop connoisseur. (I’m also known for making up great puns on the fly).”

How do we handle anger in a genuine way without turning into a jerk?

One concept that is important to understand is the difference between anger and rage. Anger is actually a useful emotion in that it is a signal for when something is not right or amiss. Anger serves to protect us from harm. Rage on the other hand is when anger runs unchecked and does harm to others. Anger can be a “check engine” light and being able to say, something is not right here. It indicates that a boundary is being violated. Jane says, “anger is a tool that God has given us to protect ourselves and also let us know when things are just not right”.

Anger as Change Agent

Anger can be a very good motivator for change. Jane gives the example of John Lewis and the civil rights movement. How we respond with love even when people are greeted with anger and disdain. The key is to be able to look beyond our own fear and see the humanity of others. That even though we might not agree with the other we see the hurt and fear of others.

It is possible to be angry with someone without it being an end to the relationship. Jane mentions that sometimes we get angry because we care about the other person. She says, “indifference is not love”. Anger has a way of signaling us that something is not right in the relationship. And we do ourselves a disservice by pretending that everything is okay.

The key to handling anger with kindness is slowing things down and being curious about what is happening with the other person.

“Legit Beef”

Jane shares listening to a radio show where people would call in and talk about what they were angry about. And the radio host would commemorate by saying “that’s legit beef” or “that’s not legit beef”. There are times when anger comes because of “legit beef”. And in some of those situations, anger is the appropriate emotion. So don’t talk yourself out of your “legit beef”, but instead allow yourself to be curious about that.

“Bless Their Hearts”

Jane tells a story about walking down the road and a truck coming by really fast and close to her. Jane shares that her first reaction was to yell and curse at the guy driving the truck. And then almost instinctively, when she recognized her own anger, was to say “bless his heart” (it’s a southern saying…). And the challenge then becomes, can we truly mean “bless their heart” as an act of compassion. That whatever the other person is experiencing, we can have compassion for them. The key to showing kindness and compassion when faced with anger is to be able to continue to see the other person as a child of God worthy of our love and kindness. We slow things down and take a minute to acknowledge the other’s humanity.

Acknowledge and Embrace Your Anger

Jane reminds us that when dealing with anger we shouldn’t try to always get rid of the anger, but to acknowledge it and learn to slow things down enough to get curious with what is happening. Then be able to say what we need in that moment and be able to connect to the other person’s humanity.

Jane shares that we don’t always succeed in dealing with our anger well, but the key again is being able to acknowledge the anger and slow things down.

Another key to dealing with anger is recognizing the dichotomy of being angry with someone and still being engaged with them. Again, it is possible to have a mixture of emotions, in other words, “both and” instead of just “either or”. The key to being able to do this well is in treating people with kindness and the work of reconciliation. We might not always see things in the same way, but we can stay engaged and be willing to listen and hear the other person’s point of view.

“Rage shames, but anger is a tool of connection”

We can share our anger with another and this has the potential of creating emotional intimacy. To share how we have been hurt or feel afraid is an act of vulnerability. And this is what creates connection and intimacy.

Jane reminds us too, that we shouldn’t turn our anger inward or try to shut it down. That is a form of inward rage and is self serving. Jane said, “that some of the kindest moments from friends has been when they have been willing to confront me”. It was an invitation to intimacy and closeness for them to be able to share what was bothering them.

“Inward rage is people pleasing. Outer rage is people shaming.”

In many ways being able to share our anger with others is an act of kindness that requires a lot of courage. When we share our anger in healthy ways it gives us the ability to connect at a much deeper level. It also is healing and reconciling.

However, in situations where it is really not safe to share your anger, it can be useful to hold back. People that have grown up in traumatic situations, such as abusive relationships, turning anger inward becomes a survival tool. But this is not sustainable and a person really should work through this with the help of a professional.

Being Polite Isn’t Always Kind

Being polite is not always the kind thing to do. There are times when we need to call things out and speak truth to things that are not right. In many ways, this was what Jesus taught and was the point of his ministry.

“Jesus came to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable”

Jane speaks of her ongoing work of reconciliation around racism. Jane reminds us that being polite has been used by white people to maintain oppression. In that we need to speak truth to injustice and that is not always pretty. And when we are willing to disrupt things, that is an act of tough love. It is an invitation to compassion.

Moral Injury

When we dehumanize others, we not only hurt them, but we hurt ourselves. We have learned this from veterans who have been in war situations where they have had to harm others. Their harm to others creates a moral injury to themselves. It goes against their core values of seeing others as human beings.

Boundaries

Jane talks about Brene Brown’s work and the importance of boundaries. Jane says that when we have good boundaries with ourselves and others, it is an act of compassion. It takes away the fear and allows us to have more freedom and autonomy. “I can have the space to have more compassion because I can say no”.

Conclusion

As counterintuitive as it sounds, the emotion of anger can be a tool for showing kindness and compassion. Anger is a signal within ourselves that something is amiss. When we are hurt or afraid we experience anger. But anger can also be a prompt for us to call out things that are not right. In that when boundaries are crossed, anger can help us to confront what is wrong. And when we handle and express our anger in healthy ways, it is a way to connect and reconcile with others. It is an act of kindness and compassion to be vulnerable enough to name what is wrong and allow people to come close.

Gordon (00:00):

Well, hello everyone. And welcome again to the podcast. And I'm so glad and thrilled for you all to get to hear from my good friend and colleague Jane Carter. Jane, welcome to the podcast.

Jane (00:14):

Thank you. I'm so happy to be here, Gordon.

Gordon (00:16):

Yes. Uh, Jane and I have known each other for a good, good bit of time now. And we've had all these divergent, uh, our, our paths have crossed in many interesting ways. First, I guess, kind of per professionally, just, uh, we had got Jane had hosted a conference in Asheville, North Carolina, the brew, your practice, uh, conference or workshop or whatever we, we, we call that thing. Uh, but also I, we found out through our conversations that we are, are both Episcopalian and, um, have a lot of church crossover as well. So Jane, I'm gonna stop talking about you and let you tell a little bit more about yourself and of your work as a therapist and a coach and all of that sort of thing.

Jane (01:05):

Yeah. Okay. Um, gosh, where to start. I'll, I'll try to be brief cuz I'm a rambler, but um, I, I love living in the mountains. Um, I love where I am. I love that you're nearby mm-hmm

Gordon (02:39):

Yes. Yes. Well, yeah. And, and I, Jane and I are of the same mold. I'm a, I'm the quintessential people pleaser I'm uh, you know, I'm curious, I, I think we talked about this before Jane, but I'm an engram two. Is that where you are?

Jane (02:58):

Are you, I'm a nine

Gordon (02:59):

You're a nine. Interesting. You're interesting. So I'll probably have to do a whole episode on the engram because that'll make, make, make more sense to people, us talking about that. But yeah. So one, one of the things that I know E even I struggle with at times is, um, which is, is I, I think something that we is is, is a struggle probably for a lot of people, is that when we're feeling angry or just downright pissed off about something, but we don't show it externally and we put on this nice face mm-hmm

Jane (03:40):

Uh, it comes sideways, huh? Anger always goes somewhere

Gordon (03:47):

Mm-hmm

Jane (03:48):

And, and anything that I'm saying here, I'm saying it to myself as much as to anyone who's listening, by the way,

Gordon (05:01):

Mm-hmm

Jane (05:01):

Gordon (05:15):

Right, right. Yeah. When I, and I just thinking about the work that I do with my clients, um, know anger comes up a lot, you know, um, mm-hmm,

Jane (06:26):

Yeah. So yes, I agree that sometimes anger really is hurt or fear coming, coming out in a certain way. And there are a lot of people, I think, especially, um, like in toxic rescue or in certain households where the only acceptable emotion is anger. So everything get filtered through that.

Gordon (06:46):

Mm-hmm

Jane (06:47):

Um, but I, I really appreciate it. I went to a, an anger workshop, um, by John Harold Lee, who's just fantastic. He wrote a great book called the anger solution and he said, and sometimes anger is anger

Gordon (07:00):

Jane (07:01):

Mm-hmm

Gordon (08:00):

Yes. Yeah.

Jane (08:01):

You know, and, and in that sense, our boundaries are what help kind of define us and define, okay, where do I end? And where does the other person begin? And so anger is a gift and that it tells me, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa. My boundary is being violated. And this is part of me. My anger is part of me. Mm-hmm

Gordon (08:19):

Mm-hmm

Jane (08:20):

Gordon (08:24):

Right, right. Yes. I, you know, I want, you know, one of the things that I think a lot of us have experienced over the last few years with, with COVID with, uh, the black lives matter movement mm-hmm

Gordon (09:23):

Sure. Particularly for, for those of us in the south, I say, and, and it's, it's universal throughout the country in the United States, but I think for, for almost there's this underlying anger, and then more recently with the, the war in Ukraine and what we see the, uh, Russian leaders, Putin, and all of them doing to innocent people, all of that is anger producing. And so what do we do with that? I mean, how do we, how do we respond? And I'm wondering this too, and I'm just kind of thinking out loud here. Sure. Jane, is that, um, are there times when it's not appropriate to be kind and compassionate and are there times when we need to be angry? Yeah, yeah.

Jane (10:14):

Yeah. Oh, that's a great question. And I, I think it depends on how you define kindness. Um, I think it's really important that we delineate between being nice or polite versus being kind mm-hmm

Gordon (10:31):

Jane (10:32):

And sometimes kindness is not polite. Sometimes kindness isn't even nice. Um, some you, I was listening, speaking of, you know, racial injustice, I was, I was listening to an interview that John Lewis did with Krista Tippet on, on being, um, this was maybe a couple years before he died. Um, and you know,

Gordon (11:05):

Jane (11:06):

Righteous, anger saying something needs to change. So again, Mo anger can be a really good motivator. It can, it can be a good thing, but they didn't succumb to hatred or rage mm-hmm

Jane (11:53):

So John Lewis was talking about how they worked so hard to connect with love and kindness for these people who were just, I mean, trying to kill them mm-hmm

Gordon (12:46):

Mm-hmm

Jane (12:47):

Stance where they said, okay, yeah, of course they felt angry. And of course you can be angry at someone who is perpetrating injustice against you. And yet, if can you have the active discipline to practice going, okay. And this person was a baby once mm-hmm

Gordon (13:21):

Yeah. Yeah. And we see that all the time's,

Jane (13:24):

I'm not angry. I'm not angry. It's fine. That's not, it's not that passivity.

Gordon (13:29):

Right. Right. Yeah. And, and it's a, you know, I, I know in my work with couples, um,

Jane (13:51):

In fact, if you were, uh, emotionally detached and, uh, was the word I'm looking for, um, and, uh, oh gosh. It's, it's just evading me. Um, yeah. Indifferent indifference is not love

Gordon (14:07):

Right.

Jane (14:07):

You know, like sometimes people feel angry because they love the, I mean, oh gosh, that could go into bad territory. Mm-hmm

Gordon (14:29):

Jane (14:34):

Again, you know, if I'm, if I'm in a couple and, or I'm working with a couple and, and someone's having a strong response again, can we slow it down enough to bring curiosity to that and say, you know, okay, well, what, what is this about? Where is it coming from? Um, is this legit anger or is this tied to something else? Um,

Gordon (14:56):

Mm-hmm

Jane (14:57):

You're gonna think I'm so weird. Gordon. I was, I was in the car with a friend and we were listening to her fatal favorite satellite radio show where people would call in and the, the, the radio guy would, what your beef is.

Gordon (15:12):

People say,

Jane (15:14):

My friend did da da, and then she, no, no, no. They would say whatever they were angry about Uhhuh and he, and his cohost would either say that is legit beef, or that's not legit beef

Gordon (15:24):

Jane (15:25):

Was the funniest show. I don't even know what it was called. Yeah. But I, I have this shorthand with some of my clients well, where I'll be like, that's legit beef. Like, don't talk yourself outta your anger quite yet.

Gordon (16:14):

Yes. That make sense. Yes. Uhhuh. Yes. So, yeah. So I I'm thinking that this might bring up, can

Jane (16:20):

I, can I take the time to connect with their humanity?

Gordon (16:23):

Yes. Yes. I I'm. I'm thinking that as you're saying this, there might be some people that are thinking, okay, what, how can I be kind with my anger? Um, yeah. And what would that look like? Yeah. Yeah.

Jane (16:39):

Um,

Gordon (17:22):

Jane (17:25):

And I'm like, like yelling cuss words to this guy who couldn't hear me obviously. And then, and I started laughing and then I was like, well, bless his heart. And cause you know, in the south we have a saying, you can say anything about anyone, as long as you say, bless her heart or bless

Gordon (17:42):

Her heart. Right, right.

Jane (17:45):

And, and I thought about it though, even in that moment, I was like, I kind of chuckled that. I, I instinctively like, it doesn't even cross my mind. I instinctively go bless his heart and it's almost become passive aggressive thing. Like I'll, you know, I'll just say that. So I don't have to say a bad thing. Um, but then I thought, you know, okay, along the lines of John Lewis, like that's kind of what they were doing. Could I sincerely say, bless his heart. I'm really angry at this person who almost ran over me and can I bless him? Can I say a little prayer that whatever he's dealing with gets healed or whatever makes him need to do that

Gordon (18:24):

Right. Is

Jane (18:25):

Healed, you know, can I take a minute to acknowledge his humanity? Know that if he walked into my counseling office tomorrow, I would immediately feel compassion for him and, and have a totally different stance. Like how can I help you? How can I be here for you? Like you are a human being. And, and so I think what helped, you know, in terms of like feeling the anger, I think again, don't just get rid of the anger or say that it's unacceptable. Can we acknowledge our anger and slow it down enough to go, okay, mm-hmm

Gordon (19:02):

You

Jane (19:02):

Know, even this is so hard, but like, am I praying for Putin?

Gordon (19:09):

Mm-hmm

Jane (19:09):

Gordon (19:35):

Mm-hmm

Jane (19:35):

Gordon (19:39):

Right, right. Yeah. You know, one, one of the things that I think, um, some people struggle with is, um, this dichotomy of emotions that comes out for us and that we think of, okay, if I'm, if I'm angry at someone or I'm angry at something, then I can't, I can't also embrace that. Or I can't also, um, you know, still stay engaged with that person or that right. That thing. And the, and the truth of the matter is the, we are capable of doing not either or, but both. And absolutely. Yeah. And so, and I think part of the thing is, is that, um, where kindness comes in, I think is when we are angry at someone that we also stay engaged with them, even though we're, we're expressing our anger. Yes. And, and, and, and we do that in a kind way where we're not belittling them as a person, but really yeah. You know, that, that, that old cliche, I, you know, I don't, I hate the sin, not the center kind of thing. Yeah, yeah, yeah. That,

Jane (20:50):

Yeah. But it's true. I mean, cliches are cliches for a reason. Right.

Gordon (20:54):

Mm-hmm

Jane (20:55):

So, I mean, I love the, um, I love the nonviolent communication model. Mm-hmm

Gordon (21:41):

Yeah.

Jane (21:42):

If I do inward rage, which is the people pleasing, I'm just gonna shove my feelings down and be really polite. Um, I am now I'm serving myself, first of all, I'm serving my own fear and self protection. Mm-hmm

Gordon (22:27):

Right,

Jane (22:27):

Right,

Gordon (22:28):

Right. Oh, I,

Jane (22:29):

Yeah. But outer rage, you know, inward rage is people pleasing. Right. Outer rage. If I blast that person to smithereens and shame them, that's not helping anyone.

Gordon (22:43):

Right.

Jane (22:43):

Certainly not creating intimacy.

Gordon (22:45):

Right. Right. Oh, I love that. I, I, I you've really helped kinda re you frame something in that. Yeah. I hadn't really thought about, um, being angry with someone in a, in a healthy way really is an act of intimacy and vulnerability and that you're, yeah. You're opening yourself up and sharing with them. Um, you're, you're internal world and, and that's a scary thing. And I think that's one reason. So many people do tend to be people pleasers is that they, yeah. They, they don't want to get that vulnerable with others.

Jane (23:23):

Sure. And, and, you know, I, I really recognize that people pleasing is often a, a survival, excuse me, for survival tools from trauma mm-hmm

Gordon (23:58):

Jane (23:59):

And, and even, you know, when I think about, you know, we've had a lot of very, very interesting political situations in my family,

Gordon (24:08):

Uhhuh.

Jane (24:09):

It's funny, my mom, and, uh, we've had a couple of moments where we were just outright kinda lost our minds and were yelling about stuff. I'm, uh, I'll say I actually am like, mom, it's actually great that we can yell at each other cuz growing up, I was such a people pleaser that I didn't. And I'm like, aren't you glad I can do anger? You can do anger. Now we can do

Gordon (24:31):

Anger together for, for

Jane (24:33):

Recovering Southern Christian women.

Gordon (24:35):

Jane (24:36):

Like, yes, it's wonderful.

Gordon (24:37):

Jane (24:38):

But you know, five minutes later we'll be like snuggling on the couch with each other. It's like, you know, I love you. I know. And I love you love me, you know that it's like, isn't it great that we love each other enough that we know we can have a political fight and not hate each other or lose respect for each other. Yes. And I, I really see that as a gift. Yes. Um, but all that to say, like if I, so, so back to like on an individual level, there's a intimacy on a, on a general level when things are happening in the world that truly are wrong or unjust

Gordon (25:13):

Mm-hmm

Jane (25:14):

Gordon (25:30):

Mm-hmm

Jane (25:31):

Gordon (25:59):

Yes.

Jane (25:59):

But I I'm okay. Being Debbie downer and saying that's, that's not okay. And, and I'm, I would say maybe 50% of the time I'm that brave. I'm still working on it, but mm-hmm

Gordon (26:22):

Say that again, Jane. Cause we say that again, Jane, we froze,

Jane (26:26):

Froze up. So I don't know who said it, but it was it's the idea. Jesus came to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.

Gordon (26:33):

Mm.

Jane (26:34):

And Jesus, wasn't always polite. And, and I think sometimes, but, and yet, and yet Jesus was very loving

Gordon (26:43):

Mm-hmm

Jane (26:45):

Gordon (27:10):

Mm-hmm

Jane (27:10):

Gordon (27:25):

Right.

Jane (27:26):

And so politeness can really preserve, you know, we white people really don't like to be uncomfortable.

Gordon (27:33):

No, that's right. That's right.

Jane (27:36):

Yeah. You know, there are people trying to outlaw that in schools right now, like don't, you dare make white people uncomfortable, but this is a, that's a whole rabbit trail I could go down. But, but all that to say, right, right. Is that, that being disrupted is often a sign of love. It's it's creating space for others to be loved who have been treated unjustly mm-hmm

Gordon (27:55):

Jane (27:56):

Um, and when others are willing to disrupt us, it's actually love, it's tough love, but it's

Gordon (28:00):

Love. Yeah. Yes. It's really a it's it's a, you, you know, as I think about it in that context, it's really an invitation to begin to, to show some compassion for others.

Jane (28:14):

Yeah,

Gordon (28:14):

Yeah. Yeah. And if

Jane (28:17):

I love, I love how you put that Gordon. And when we invite others, to be more compassionate, that in itself is an act of kind. I mm-hmm

Gordon (28:33):

Yes. Uhhuh

Jane (28:34):

Gordon (28:48):

Yes, yes, absolutely.

Jane (28:50):

And so if someone is willing to call me out for not being compassionate or for being degrading to humanity, the humanity of someone else, they're actually helping me too. Yes. But of course, with the other person.

Gordon (29:04):

Right. And my, of just, uh, having worked with, um, with some veterans and that sort of thing yet, just that, that moral injury phenomenon is something you see with, with veterans that where they've been their in war and they're having to harm other people when it just goes against their, you know, with they, what they feel and believe totally internally. So, I mean, that's just, again, that's a whole rabbit trail. We could go down. Sure. We're just talking about that time. Well,

Jane (29:36):

You know, bring it, I mean, Episcopalians gotta keep, bring it back. And if, you know, I've been taught that if I, even if I hate someone, if I see them as less than human mm-hmm, I might as well have killed them. Like, it's that that's the as murder, right. Uhhuh mm-hmm

Gordon (30:16):

Yes. This is. And I, again,

Jane (30:17):

I don't wanna claim to have solved it. Like this is a lifelong,

Gordon (30:21):

Right.

Jane (30:23):

But can I, again, can I kind of okay. Bless your heart.

Gordon (30:28):

Yeah.

Jane (30:29):

Can I be really angry at someone? And even if I hate them sometimes can I reconnect with, and this is a human being.

Gordon (30:37):

Yes. Yes. And to me that's the, when we can do that and we might not do it well, we might, might be really messy and not, might not be a hundred percent when we do that. But I think when we do that, that is when we, we practice kindness and compassion towards others.

Jane (30:56):

And I I'll bring it back too, to the idea of boundaries. Mm-hmm

Jane (31:54):

Once you have a fence, which is a boundary, the dogs can run free and be happy and playful and be themselves mm-hmm

Gordon (32:28):

Right, right.

Jane (32:30):

I, I can have the space to be more compassionate because I know I can say no to someone.

Gordon (32:35):

Right, right. Oh man. I love this stuff. I love this stuff. And you know, I, I've gotta be respectful of your time. Uh, Jim, but, uh, yes, I know. I know, but we, this, this will end up being a really, really long episode, but

Jane (33:17):

Um, the easiest way to reach me is, uh, you can email me at Jane Jane Carter, coaching.com, or my website is Jane Carter, coaching.com. I'm on Instagram at Jane Carter coaching. Uh, it's mostly business related stuff. Mm-hmm

Gordon (33:34):

Yes, yes. And, and Jane, uh, we we'll have all this in the show notes and the show, so summary for people so they can connect and find you. Um, so yeah, so we'll do this again.

Jane (33:47):

Awesome. This is Gordon. You.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

About

L. Gordon Brewer Jr., LMFT |Podcast Host – Gordon has spent his career in helping professions as a licensed therapist, counselor, trainer, and clergy person. He has worked with 100’s of people in teaching them the how to better manage their emotions through self-care and the practices of kindness and compassion. Follow us on Instagram and Facebook . And be sure to subscribe to our newsletter.

In this episode Gordon talks with Jenn Fredette, LPC, MA, MDiv, about being vulnerable, being human and coping with people we just don’t agree with. Jenn shares her experience of having come from a very conservative religious background (“cult”) and the ways in which she has grown and healed since then. Jenn and Gordon also talk about how being present with and for people is an act of kindness and compassion.

In this episode Gordon talks with Jenn Fredette, LPC, MA, MDiv, about being vulnerable, being human and coping with people we just don’t agree with. Jenn shares her experience of having come from a very conservative religious background (“cult”) and the ways in which she has grown and healed since then. Jenn and Gordon also talk about how being present with and for people is an act of kindness and compassion.

Gracie and Jody Davis met while working at summer camp in college. Their love for the outdoors and the camp community inspired their work together. After working for the Episcopal church in varying capacities, Gracie and Jody were honored to accept the job of

Gracie and Jody Davis met while working at summer camp in college. Their love for the outdoors and the camp community inspired their work together. After working for the Episcopal church in varying capacities, Gracie and Jody were honored to accept the job of

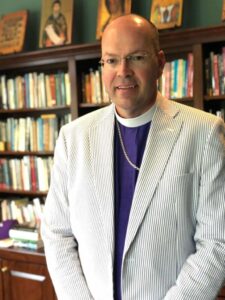

In this episode, Gordon talks with The Right Rev. Brian Cole, the bishop of the

In this episode, Gordon talks with The Right Rev. Brian Cole, the bishop of the  A southeast Missouri native, The Right Rev. Brian Cole graduated from Murray State University in Murray, Kentucky, with a Bachelor of Science degree in Business Administration in 1989. In 1992, he earned a Master of Divinity at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, with additional studies in Anglican Church History at The University of the South School of Theology, Sewanee, in 2001. He also pursued studies in Art and Prayer at General Theological Seminary (GTS), New York City, in 2006, and studied liturgics In Asheville, N.C., from 2002 to 2005.

A southeast Missouri native, The Right Rev. Brian Cole graduated from Murray State University in Murray, Kentucky, with a Bachelor of Science degree in Business Administration in 1989. In 1992, he earned a Master of Divinity at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, with additional studies in Anglican Church History at The University of the South School of Theology, Sewanee, in 2001. He also pursued studies in Art and Prayer at General Theological Seminary (GTS), New York City, in 2006, and studied liturgics In Asheville, N.C., from 2002 to 2005.

Mallory McDuff teaches environmental education at Warren Wilson College where she lives on campus with her two daughters. She’s the author of four books, including her most recent:

Mallory McDuff teaches environmental education at Warren Wilson College where she lives on campus with her two daughters. She’s the author of four books, including her most recent: